Most analysts consider the euro to be a single currency, issued by a single central bank, the “European Central Bank” or ECB for short. In reality, the ECB is as much a Central Bank as the Federal Reserve is Federal and the euro is merely a single name for 19 distinct currencies pegged to one another in a 1:1 ratio. Sounds crazy? Well, let’s check out the “source code” and see what we can find out.

While it is pretty easy to draw the above conclusions, they raise a lot of questions about their consequences. Is it possible to dismantle the euro? How are monetary decisions actually made? Who are the officials who make these decisions, what is their exact mandate when, in which role and under which circumstance? What are the consequences of the gigantic imbalances within the cross-border euro settlement system for the countries and central banks involved?

In this article, only the basic system is examined with the hope that this insight might help to answer some of the many open questions regarding the euro, the Eurosystem and it’s cross-border settlement and payment system.

Introduction

If there is one thing I learned from my experiences in the battle against software patents in Europe is that the EU technocrats are absolute masters in obfuscating the true details and meaning of whatever they write about, which puts a lot of people on the wrong foot. Almost everyone thinks that the ECB is the central bank of the euro-area and that it is the single issuer of a single currency, the euro. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Having been a professional programmer for 10 years, I’ve learned to look at the source code, whenever you find that the documentation you are provided with is unclear, since the source code is the one document which contains each and every detail. When you read the “source code” of the EU, it’s treaties, you find many of the principles laid out in the “How To Write Unmaintainable Code” guide. It is clear that the writers of the EU “source code” understand the general principles of “obfuscation” very well:

“To foil the maintenance programmer, you have to understand how he thinks. He has your giant program. He has no time to read it all, much less understand it. He wants to rapidly find the place to make his change, make it and get out and have no unexpected side effects from the change.

Of course, most of the methods applied in the art of writing unmaintainable code cannot be applied in legalese, but some of them work just fine:

“Much of the skill in writing unmaintainable code is the art of naming variables and methods. They don’t matter at all to the compiler. That gives you huge latitude to use them to befuddle the maintenance programmer.”

“Use acronyms to keep the code terse. Real men never define acronyms; they understand them genetically.”

“Reuse Names – Wherever the rules of the language permit, give classes, constructors, methods, member variables, parameters and local variables the same names. The goal is to force the maintenance programmer to carefully examine the scope of every instance.”

As an example with respect to reusing names, since 2009 we have a completely different “EU” than before. You see, with the Lisbon Treaty “the EU” gained “legal personality”, which it did not have before. So, in 2009 “the EU” became a legal entity, more or less a corporation, whereby it essentially changed from a confederation of independent states into a supra-national legal body. And because the French and Dutch did not like the idea of having European constitution and supra-national “EU” a few years earlier, this monumental change has simply been obfuscated and re-written as a mere “amendment” to the Treaty of Rome:

So, you delete a word and you “repackage” a bit and voilà, you have a federal Europe, without having to bother to even ask the people whether they like it or not…

The “source code” for the ECB

At first glance, when we consult Wikipedia, it seems that the ECB is a central bank and all is well:

Let us first note that the ECB has been established in 1998, while the “single” euro currency itself was introduced in 1999:

“The euro was introduced to world financial markets as an accounting currency on 1 January 1999, replacing the former European Currency Unit (ECU) at a ratio of 1:1 (US$1.1743). Physical euro coins and banknotes entered into circulation on 1 January 2002, making it the day-to-day operating currency of its original members, and by May 2002 had completely replaced the former currencies.”

The national currencies of the eurozone “ceased to exist independently” because their “exchange rates were locked at fixed rates against each other”, even though they continued to be used as legal tender until 2002. A fine example of the art of camouflage. What is suggested is that by locking the exchange rate of a number of currencies at fixed rates to one another, the national currencies ceased to exist all together and one magically obtains a “single” currency, “the” euro.

In reality, however, the number of currencies in existence remained exactly as it was before. All what really changed is the exchange rates between these currencies being fixed and no longer variable. Of course, it is formally correct to state that these currencies are thus no longer independent. However, by no means does this imply that the German Central bank, for example, could as of then suddenly issue Dutch Guilders, French Francs or Italian Lira. Also, by no means does this imply that euro notes issued by the German Central Bank, for example, are equal to the ones issued by the Dutch, French, Portuguese or Italian Central Banks. What’s more, by no means does this imply that the so-called European Central Bank can even issue any currency!

The X-factor

In fact, both euro coins and euro notes are eXclusively issued by the National Central Banks and the issuer is clearly marked in both cases:

When consulting Wikipedia about this, we read:

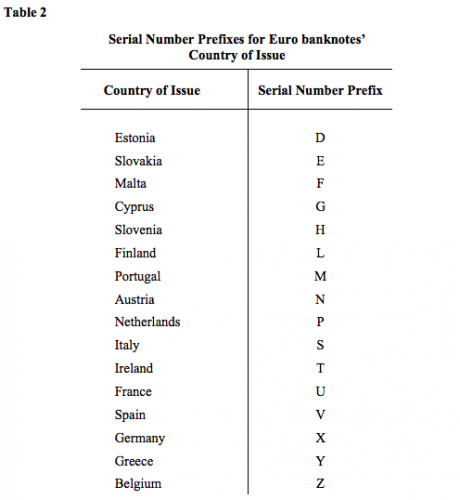

Unlike euro coins, euro notes do not have a national side indicating which country issued them. The country that issued them is not necessarily where they were printed. The information about the issuing country is encoded within the first character of each note’s serial number instead.

The first character of the serial number is a letter which uniquely identifies the country that issues the note. The remaining 11 characters are numbers which, when their digital root is calculated, give a checksum also particular to that country.

Note that not only has no prefix been assigned to the ECB, no prefix has even been reserved for the ECB!

So far, it is clear that the mere exercise of “fixing” the exchange rate of a number of currencies did not magically create a “single” currency. It is also clear that the ECB cannot issue coins nor notes, while the coins and notes issued by the National Central Banks are still clearly separated from one another.

In other words: all what really changed with the introduction of “the” euro is that the old national currencies were all re-branded to “euro”, whereby at the same time the already fixed exchange rates were normalized to 1, resulting in 19 distinct currencies all bearing the same name having been pegged to one another in a 1:1 ratio. The ultimate example of the art of re-using names for 19 distinct “currencies” to make it pretty much impossible for the “maintenance programmer” to figure out which “euro” is which.

And since the ECB cannot issue euro coins nor notes, one cannot help but ask the question: How can the ECB be a central bank if it cannot issue any currency?

The Euro System

Besides the ECB, we have the Euro System, “Not to be confused with the European System of Central Banks”:

Note that unlike the ECB, the Eurosystem is a collective of member states and therefore has no legal personality in and of itself. And, contrary to what one would expect from a central bank, the ECB does not have the monetary authority of the eurozone, although at least one specific monetary authority task has been delegated to the ECB, namely the right to authorise the issuance of euro banknotes and, allegedly, coins.

Article 16, “Banknotes”, of the Statute of the ECB reads:

“In accordance with Article 128(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, the Governing Council shall have the exclusive right to authorise the issue of euro banknotes within the Union. The ECB and the national central banks may issue such notes. The banknotes issued by the ECB and the national central banks shall be the only such notes to have the status of legal tender within the Union.”

Interestingly, the word “coin” is not to be found in this document, but let’s continue with the Eurosystem:

Once again, contrary to what one might expect from a central bank, the ECB does not apply monetary policy.

A central bank which does not have monetary authority, cannot issue currency and does not apply monetary policy?

And what about this European System of Central Banks which we should not confuse with the Eurosystem?

There used to be some explanation about this all at the site of the ECB which has now gone. Archive.org to the rescue. From the horses mouth:

“The legal texts which established the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) – the Maastricht Treaty and the Statute of the ESCB of 1993 – were written on the assumption that all EU Member States will adopt the euro and that therefore the ESCB will conduct all the tasks involved in the single currency. However, until all EU countries have introduced the euro, it is the “Eurosystem” which is the key actor. The term “Eurosystem” covers the ECB and the national central banks of those EU Member States that have adopted the euro. Until now an unofficial term, it is mentioned for the first time in the Lisbon Treaty (Article 282 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union).”

“The Eurosystem as the central banking system of the euro area comprises:

* the ECB; and

* the national central banks (NCBs) of the 18 EU Member States whose common currency is the euro.”

“The Eurosystem is thus a sub-set of the ESCB. Since the ECB’s policy decisions, such as on monetary policy, naturally apply only to the euro area countries, it is in reality the Eurosystem, which, as a team, carries out the central bank functions for the euro area. In doing so, the ECB and the NCBs jointly contribute to attaining the common goals of the Eurosystem.”

Why a system instead of a single central bank?

There are three main reasons for having a system of central banking in Europe:

* The Eurosystem approach builds on the existing competencies of the NCBs, their institutional set-up, infrastructure, expertise and excellent operational capabilities. Moreover, several central banks perform additional tasks beside those of the Eurosystem.

* Given the geographically large euro area and the long-established relationships between the national banking communities and their NCB, it was deemed appropriate to give the credit institutions an access point to central banking in each participating Member State.

Welcome to Technocrat Europe, were we actually managed to have “an unofficial term”, which was “mentioned for the first time” in a Treaty and thus became “an official term”, which, “as a team”, “in reality”, forms “the key actor” carrying out “the central bank functions for the euro area”. And of course the main reason for having “a system of central banking” is that because not all EU member states joined the euro, there is no such thing as a central (monetary) authority for the eurozone. After all, it was assumed all EU Member States would adopt the euro. And until that happens, there can be no single authority and therefore no single currency either, at least not within the framework of current EU Treaties. And that is why the ECB cannot be a real central bank which can actually issue currency, even though it’s right to do so has been formally reserved.

Ultimately, the central (monetary) authority for the eurozone is either distributed amongst the member states which use the euro currency or it is centralized within the EU or an institution thereof. And since it’s the Eurosystem which “in reality” carries out the central bank functions, the ECB is as much a central bank as the Federal Reserve is Federal indeed and remains to be that way until all EU members decide to opt-in to the euro currency.

The Target

So far, it is clear that the ECB is not a central bank and that, at least in physical form, the euro is not a single currency but 19 distinct currencies pegged to one another in a 1:1 ratio. However, much more currency exists in digital form than exists in physical form. So, if this is all true, wouldn’t there be some kind of international settlement system, which takes care of international currency transfers within the euro zone, such that all the 19 pegged currencies are indeed separated under the hood?

Yep. It’s called TARGET2:

TARGET2 (Trans-European Automated Real-time Gross Settlement Express Transfer System) is the real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system for the Eurozone, and is available to non-Eurozone countries. It was developed by and is owned by the Eurosystem. TARGET2 is based on an integrated central technical infrastructure, called the Single Shared Platform (SSP).

More about TARGET in this document from the ECB itself. Page 99:

A simple explanation of how TARGET2 works, from a Bloomberg article:

Now why would cross-border payments within a single currency zone have to be channeled via central banks, if the euro really were, well, a single currency?

Reader Lars at MishTalk puts it this way:

On this same page we read that the not-a-central bank institution called ECB also needs to work trough TARGET if it wants to make purchases within the euro zone, once again from the horses mouth:

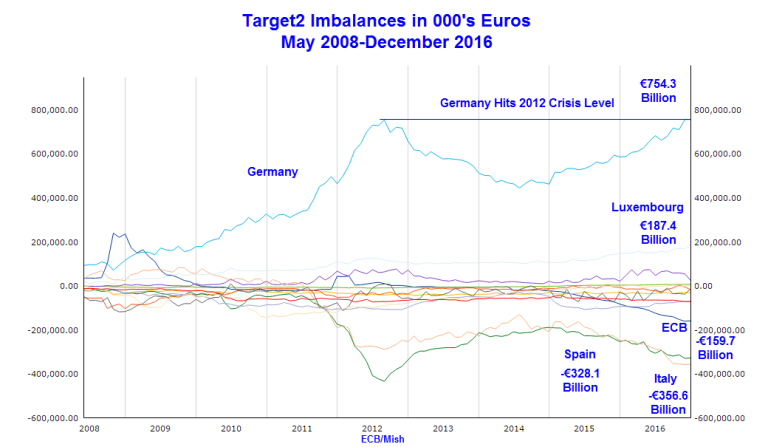

So, what happens when there is virtually no limit to how big these “target” imbalances can become and you have this system up and running for 15+ years?

Well, the “imbalances” grow into the hundreds of billions, as shown in Mish’s article:

Note that the so-called “Central Bank” ECB owes close to €160bn to the National Central Banks.

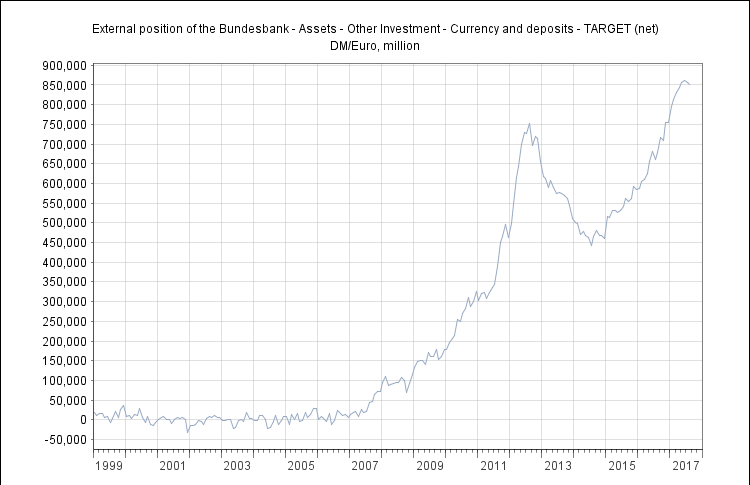

These numbers were from 2016. A check of the Bundesbank Target2 Balance as of August 31, 2017 shows this has now grown to €853 billion, which is shown in the following graph from the Bundesbank website:

Based on this, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard at the Telegraph notes the unpayable debts and asks Are Eurozone Central Banks Still Solvent?

“Vast liabilities are being switched quietly from private banks and investment funds onto the shoulders of taxpayers across southern Europe. It is a variant of the tragic episode in Greece, but this time on a far larger scale, and with systemic global implications.”

“There has been no democratic decision by any parliament to take on these fiscal debts, rapidly approaching €1 trillion. They are the unintended side-effect of quantitative easing by the European Central Bank, which has degenerated into a conduit for capital flight from the Club Med bloc to Germany, Luxembourg, and The Netherlands.”

“This ‘socialization of risk’ is happening by stealth, a mechanical effect of the ECB’s Target2 payments system. If a political upset in France or Italy triggers an existential euro crisis over coming months, citizens from both the eurozone’s debtor and creditor countries will discover to their horror what has been done to them.”

“The Target2 system is designed to adjust accounts automatically between the branches of the ECB’s family of central banks, self-correcting with each ebb and flow. In reality, it has become a cloak for chronic one-way capital outflows.”

“Private investors sell their holdings of Italian or Portuguese sovereign debt to the ECB at a profit, and rotate the proceeds into mutual funds Germany or Luxembourg. “What it basically shows is that monetary union is slowly disintegrating despite the best efforts of Mario Draghi,” said a former ECB governor.”

“The Banca d’Italia alone now owes a record €364bn to the ECB – 22pc of GDP – and the figure keeps rising.”

“Spain’s Target2 liabilities are €328bn, almost 30pc of GDP. Portugal and Greece are both at €72bn. All are either insolvent or dangerously close if these debts are crystallized.”

Central banks which are “either insolvent or dangerously close”. It’s probably nothing. What could go wrong?

Conclusions and further thoughts

After examining some of the euro’s “source code”, we can come to the following concusions:

- The ECB is not a central bank, since it does not have monetary authority, cannot issue currency and does not apply monetary policy.

- “The” euro is not a single currency but consists of 19 distinct currencies all bearing the same name and pegged to one another in a 1:1 ratio.

- The “pegging” settlement system, TARGET2, makes clear that all cross-border transactions within the eurozone are channeled trough the national central banks, including those of the ECB, as can be expected in a system of 19 pegged currencies with 19 “national” central banks but no “central” central bank.

This raises many further questions, like:

- If there is no central monetary authority within the euro system, how are monetary policy decisions actually made?

- Which official is responsible for which decision under which role?

- What consequence does this have for the legal status and enforceability of any (monetary policy) decision by either the ECB or the Eurosystem?

- What power does the ECB, the Eurosystem or the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) have to enforce “it’s” policy decisions upon the National Central Banks, in the current system whereby “in reality” a not institutionalized “team” carries out the central bank functions without any central authority whatsoever?

- What happens when one of the “team” members for one reason or the other decides to refuse to carry out instructions by the “team” or the ECB?

- What happens to the “imbalances” should one of the “team” members decide to or be forced to leave?

While it’s pretty much impossible to answer these questions without doing a lot of research, it is my hope the contents of this article may be helpful to those interested in performing further research on this complicated topic.

Picture credits: Leon Baten private collection

Original article can be found here, and processed by Leon Baten